Arcs

The two gigantic stellar arcs are unique, and unutterably beautiful at all magnifications

Two Unique Arcs

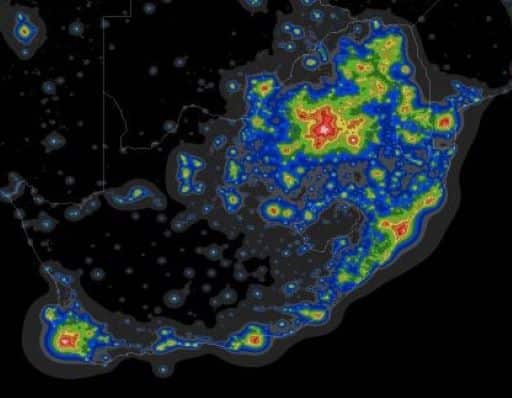

Two large arcs of young stars and clusters are prominently situated in the northeast corner of the Large Magellanic Cloud. The enormous arcs are unique: the stars within each arc are practically coeval, and the arcs are parts of perfect circles, hence the names they were given by Efremov & Elmegreen (1998) – the Quadrant, whose stellar associations form a perfect quarter part of a circle, and the Sextant, whose stellar associations form a perfect sixth part of a circle.

The Quadrant lies at the southern end of the gigantic supergiant shell, LMC 4. It spans an incredible ~980 light-years, and the ages of the stars and clusters within it are within 12–20 Myr (Efremov, 2012). It consists of the huge OB association LH 77, which has an older stellar population as it has already expelled its ambient gas, and astronomers believe it has most likely contributed to the formation of LMC 4. The smaller LH 65 and LH 84 lie within LH 77’s western and eastern ends respectively.

The Sextant lies slightly to the southwest of the Quadrant and on LMC 4’s southern rim. Its arc spans 650 light-years and the ages of the stars and clusters within it are within 4-7 Myr (Efremov, 2012). The Sextant consists of LH 51, LH 54, LH 60 and LH 63. Being younger than the Quadrant, the Sextant is surrounded by H II regions, and it contains two superbubbles, one at either end (N51D on the western end, N51A on the eastern).

The two unique and spectacular arcs. DSS image

The Quadrant was first noted by Westerlund and Mathewson (1966), who recorded on a UV plate “the great arc of the bright blue stars,” saying that “Shapley called this arc Constellation III”. However, this was incorrect, as McKibben Nail & Shapley (1953), designated LH 63 = NGC 1974, which is located within the Sextant arc, as the identifier of Constellation III. They also noted that Constellation III is a triple cluster.

Similar arcs of star clusters have not been reported elsewhere. The only thing resembling the Quadrant and Sextant stellar arcs is a large region in the galaxy NGC 1620 studied by Vader & Chaboyer (1995), although it was noted (Efremov & Elmegreen, 1998) that at the inclination of this galaxy, it is difficult to tell if this is a triggered arc or a spiral arm.

There is a great mystery surrounding the giant stellar arcs’ origin, one that has been discussed since 1966. Many hypotheses have been advanced to explain them but the mystery remains unsolved; their origin both a controversial issue, and an important unsolved problem. Personally, I think Winston Churchill’s famous quote (when he described Russia) best describes these glorious arcs: “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

Observing the Arcs

It is absolutely superb observing these two exotic arcs at all magnifications, beginning with a pair of binoculars! The Quadrant is so gigantic and star-filled that it is clearly visible as a shimmering arc in 10×50 binoculars. Lacking any nebulosity and saturated with stars, the Quadrant, like all star clouds, gives up its stellar secrets in stunning fashion with increasing magnification.

The Quadrant. Image: Aladin JPG

The smaller Sextant too, is plainly visible in my 10×50 binoculars as a small, glowing arc. And in the telescope, the Sextant is absolutely beautiful. Its smaller size, fewer stars, two superbubbles and intricate nebulosity make it a very different, but equally superb, observing experience to the sparkling Quadrant.

The Sextant. Image: Aladin JPG

Scrollable Table

Location: LMC = Supergiant Shell. S/P = Southern Periphery