The LMC in the words of its greatest observers

Seeing the Cloud through the eyes of Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, James Dunlop and John Herschel

Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille

Born: 15 March 1713, Rumigny, France

Died: 21 March 1762, Paris, France. He is buried in the vaults of the Mazarin College, now the Institut de France in Paris.

Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille

French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille spent two years (1751–53) in the Cape of Good Hope surveying the southern skies. Using a tiny half-inch (1.3-cm) refractor, he discovered 24 new nebulae and clusters, charted the positions of nearly 10,000 stars, delineated 14 new constellations, and divided up Argo into three smaller ones. He discovered the Tarantual Nebula, and included it in his 1755 catalogue as Class I No. 2 and described it as “like the former [NGC 104: “like the nucleus of a fairly bright comet”] but faint”.

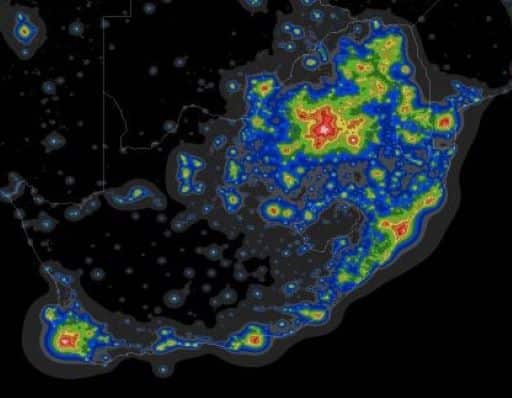

Among his new constellations was Montagne de la Table to commemorate Table Mountain near Cape Town, South Africa, from where he catalogued the southern stars. (It was Latinized to Mons Mensae on the second edition of 1763; in1844 John Herschel proposed shortening it to Mensa, and Francis Baily adopted this suggestion in his British Association Catalogue of 1845.) Mensa contains part of the Large Magellanic Cloud, which gives Mensa the appearance of being capped by a white cloud, like the so-called ‘table-cloth’ cloud that is seen over the real Table Mountain ‘at the approach of a violent south-easterly wind’ as Lacaille put it.

In 1756 he published his Planisphere contenant les Constellations Celestes, and marked the Magellanic Clouds as le Grand Nuage and le Petit Nuage.

In his words…

As a result of examining several times with a telescope . . . those parts of the Milky Way where the whiteness is most remarkable and comparing them with the two clouds common called the Magellanic Clouds, which the Dutch and Danes call the Cape Clouds, I saw that the white parts of the sky were similar in nature, or that the clouds are detached parts of the Milky Way, which itself is often made of separated bits. It is not certain that the whiteness of these parts is caused, according to received wisdom, by clusters of faint stars more closely packed than in other parts of the sky, whether of the Milky Way or of the Clouds, I never saw with the … telescope anything but a whiteness of the sky and no more stars than elsewhere where the sky is dark. I think I may speculate that the nebulosities of the first kind are nothing more than bits of the Milky Way spread round the sky, and that those of the third kind are stars, which by accident are in front of luminous patches.

James Dunlop

Born: 31 October 1793, Dalry, Ayrshire, Scotland.

Died: 22 September 1848, Boora Boora near Gosford in New South Wales. He is buried within the grounds of St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Kincumber, New South Wales.

James Dunlop

Scottish astronomer James Dunlop was the first to catalogue the Large Magellanic Cloud. He had arrived in Sydney in 1821 to serve as assistant (and maintain the astronomical instruments) at the private observatory Sir Thomas Brisbane built to explore the southern skies. German astronomer Christian Carl Ludwig Rümker was the observatory’s chief astronomer. From 1823 to 1827 Dunlop carried out some 40,000 observations and catalogued 7,385 stars, completing the Parramatta Catalogue of Stars.

Dunlop left the observatory in April 1826, moving to Hunter Street, Parramatta. Observing with a 9-inch aperture speculum-mirror reflector that he had built, he compiled his catalogue, recording 621 clusters and nebulae. He published A Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars in the Southern Hemisphere observed in New South Wales in 1828. His catalogue is very significant as it is the first catalogue of objects in the two Magellanic Clouds, and it also contains particularly handsome and accurate sketches of each Cloud.

Dunlop returned to Scotland in 1827, but sailed back to Australia when he was appointed Superintendent of the Parramatta Observatory in 1831. However, due to lack of funding, the observatory and equipment fell into disrepair, and this, along with his health failing, led Dunlop to resign his post in 1847.

In his words…

The figure of the Nebula Major is so irregular, and divided into so many parcels, that without the assistance of letters of reference it will be impossible for me to attempt a description. However, the construction and appearance of the different nebulae are more minutely described in the general catalogue. I will here only attempt to describe the apparent connection of one portion or branch of the nebulous matter with another.

I find the existence of extensively diffused faint nebulosity throughout a great portion of this quarter of the heavens, from the Robur Caroli [Charles’ Oak, a defunct constellation that Edmond Halley put into the southern sky in 1678 to commemorate the oak tree in which his monarch King Charles II hid after his defeat by Oliver Cromwell’s republican forces] to the Nebula Major, and I can even trace its existence in the vicinity of Nebula Minor.

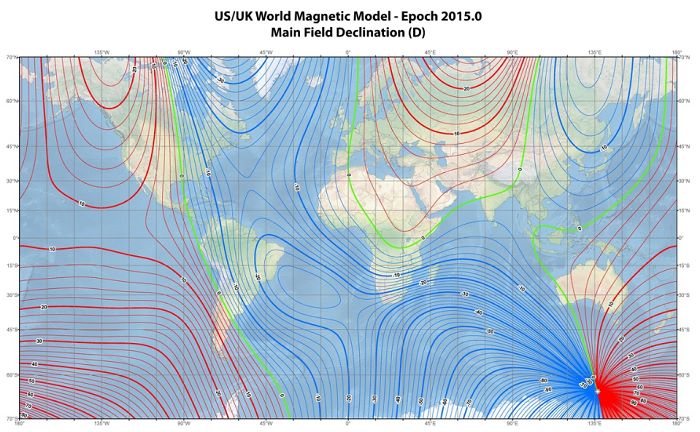

The Nebula Major is situated between 4h 46′ and 6h 3′ in right ascension, and between 66° 30′ and 71° 30′ of south declination; but the body or principal portion of the nebula is situated between 5h 71 and 5h 40′ in right ascension, and between 69° and 71° of south declination, and is composed of very strong bright nebula, very rich in small nebulae and clustering stars of all the variety of small magnitudes: I compared this portion of the nebula with Sobieski’s Shield, which in this latitude is near the zenith. The observation says, “The Nebula Major very much resembles the brightness in Sobieski’s Shield; it is scarcely so large, but I think it is equally bright.” Another observation says, “The ridge or brighter portion of Nebula Major is more condensed than the Shield.” Plate V. is a correct representation of Nebula Major.

The bright ridge or body of the nebula is extended obliquely to the equator, north preceding and south following, and the following extremity breaks off rather suddenly, faint, decreasing in brightness in a south following direction to the distance of fully a degree and a half towards the star, which is slightly involved in the narrow extremity: preceding the star markedly, a considerable increase of the brightness of the nebulous matter takes place; another accumulation takes place at § about 15′ diameter. There is a small star north with a small nebula preceding, but neither of them are involved in the accumulation of the nebulous matter. § and s are connected by streams of unequal brightness, s is pretty large and is rich in small stars and nebulae: opposite S and s, towards the principal body of the nebula, the nebulous matter is very faint and of unequal brightness; £ is south following a beautiful group of nebulae of various forms and magnitudes, on a ground of strong nebulosity common to all, with the 30 Doradus (Bode) in the centre.

South of the 30 Doradus a pretty bright accumulation of the nebulous matter takes place, extended, preceding and following, and is joined by pretty strong nebula to the arm «, which proceeds in a northerly direction from the body of the nebula; the bright star near the north extremity of the arm is not involved in the bright nebula. Between the arms and the nebula is very faint, and the bright accumulations of the nebulous matter on the north side are all connected together by nebulosity of various brightness, and are connected to the main body by the arms x and X connected by very faint nebula with the group surrounding the 30 Doradus. The accumulation of the nebulous matter at l is connected with the preceding extremity of the body of the nebula, by nebula increasing in brightness towards the neck of the body, but I cannot say that the is connected with the Two arms proceed from the neck towards the south, which are connected by faint nebula between them, which gradually increases in brightness towards the junction of the arms ; between the arm y and the body the nebulosity is faint, of various shades of brightness, and from the arms n and to the head f, the nebulosity is of various degrees of brightness.

I have made a very good general representation of the various appearances of the milky way, from the Robur Caroli to where it crosses the zenith in Scorpio. Plates VI. VII. and VIII. This was generally made by the naked eye, except in particular places where I suspected an opening or separation of the nebulous matter, when I applied the telescope. However, the dark space on the east side of the Cross, or the black cloud as it is called, is very accurately laid down by the telescope: the darkness in this space is occasioned by a vacancy or want of stars ; it contains only two or three of the 7th magnitude, and very few of the 8th or 9th magnitude. I may here remark that the Nebula Minor is not so bright as the Nebula Major.

Neither of the two nebulae, Major and Minor, are at present in the place assigned to them by Lacaille; and it has been suspected that nebulous appearances change their form and also their situation. Yet, although the situation of these nebulae, as given by Lacaille and compared with their present situation, would be favourable to such a surmise, still we must consider the dimensions of the instruments with which he made his observations, and make a reasonable allowance.

However, the 30 Doradus is at present involved in pretty strong and pretty bright nebula, and is also situated very near the brightest part of the Nebula Major; and it would be singular if its relative situation was the same when Lacaille observed it as it at present i s ; that he should have assigned to it a place in the Dorado and not in the Nebula Major, to which, from its nature, it was not only nearly allied, but in which it was actually involved. This circumstance, it must be confessed, is favourable to the conjecture ; and the 47 Toucani is similarly situated, with respect to distance, from the Nebula Minor, although it is not involved in nebulosity or connected with the nebula.

When reflecting on these circumstances, I was led to examine the present state of these nebulae and find that scarcely any nebulae exist in a high state of condensation, and very few in a state of moderate condensation towards the centre. A considerable number appear a little brighter towards the centre, and several have minute bright points immediately at the centre. Others have small or very minute stars variously situated in them, but many of those bright points in, or near, the centre may be stars, for the Nebula Major in particular is very rich in small stars. But the greater number of the nebulae appear only like condensations of the general nebulous matter, into faint nebulae of various forms and magnitudes, generally not well defined; and many of the larger nebulous appearances are resolvable into stars of mixed small magnitudes ; and a great portion of the large cloud is resolvable into innumerable stars of all the variety of small magnitudes with strong nebula remaining, very similar to the brighter parts of the milky way. And whether the remaining nebulous appearance may not be occasioned by millions of stars disguised by their distance, is what I cannot say.

But a critical examination of these nebulae would not only be a valuable treasure for the present generation to possess, but an invaluable inheritance for them to transmit to posterity. For it must be by the comparison of observations, made at distant periods of time, that we can draw any satisfactory conclusions concerning the breaking up or the greater condensation of the nebulous matter. It seems beyond a doubt that stars must assume a nebulous appearance when situated at immense distances; but whether all nebulous appearances are occasioned by stars, is a problem apparently beyond the reach of man to resolve, without the assistance of analogy, which ought not to be trusted too freely, especially with objects almost equally beyond the reach of our hands and telescopes. Several of the very faint and delicate nebulae can be resolved into stars, and also many of the brighter nebulae are composed of stars: but there are a greater number which have not yet been resolved or shown to consist of stars; and it is not improbable, that “ shining matter may exist in a state different from that of the starry.

John Herschel

Born: 7 March 1792, Slough, Buckinghamshire, England

Died: 11 May 1871, Collingwood, his home near Hawkhurst in Kent. He was given a national funeral and buried in Westminster Abbey.

John Herschel

On 16 January 1834, after a two month voyage from Portsmouth on the Mount Stuart Elphinstone docked in Cape Town, South Africa, the Herschel party disembarked – John, his wife Maggie, three children, a mechanic named John Stone, and a nurse… along with a reflecting telescope of 18½ inches clear aperture and 20-feet focal length and a telescope of five inches aperture and seven feet focal length.

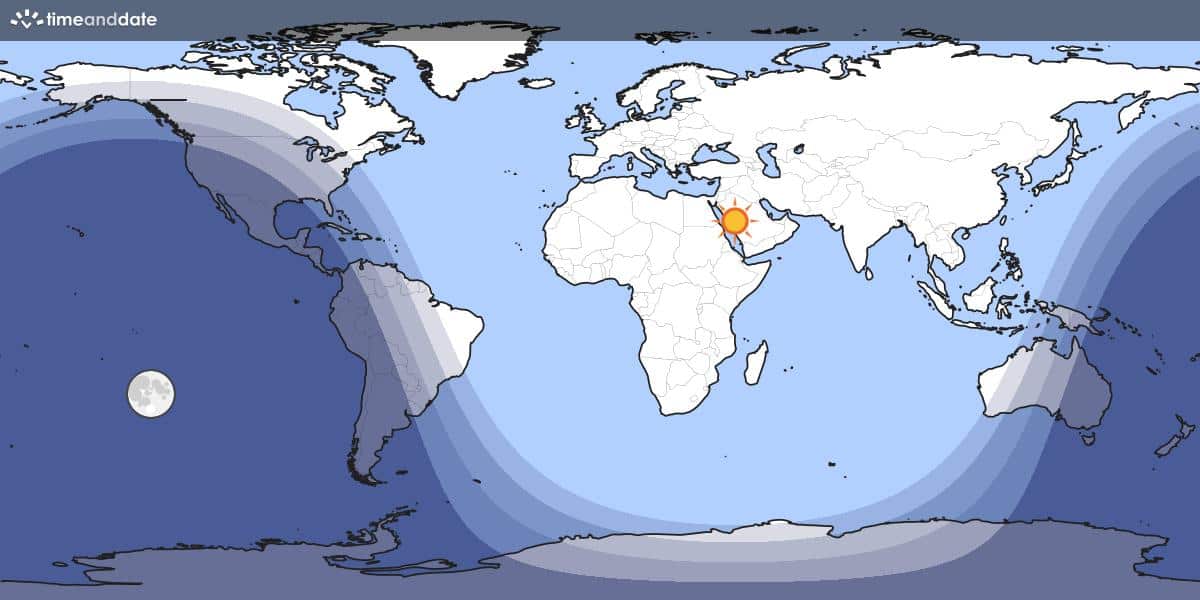

Herschel rented and subsequently bought Feldhausen, a house six miles outside of Cape Town at the foot of Table Mountain. Within less than six weeks he and John Stone had the reflector erected on a spot now marked by a memorial obelisk, “… that on the 22nd of February I was enabled to gratify my curiosity by a view of aCrucis, the nebula about h Argus, and some other remarkable objects, in the 20-feet reflector; and, on the night of the 5th of March, to commence a regular course of Sweeping.” In total, he performed 342 sweeps; his observations being executed “…in the absence of the moon, on all occasions when weather permitted, and the definition of the stars was such as to render it worthwhile to do so.”

Herschel returned to England in 1838. His monumental survey of the southern skies was published nearly a decade later, in 1847, in a volume titled, Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope; being the completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825. The catalogue lists 1,707 nebulae and clusters and 1,202 double stars and is enriched with over sixty exquisite engravings. He paid particular attention to the Magellanic Clouds, cataloguing 244 objects (stars, nebulae and clusters) in the SMC and 919 in the LMC of of which 240 are classified as nebulae, 37 as clusters, nine as clusters or nebulae, and the rest are stars. He sketched the Clouds with extraordinary insight. He concluded the first chapter with a superb description of the Magellanic Cloud.

In his words…

The Nubecula Major, like the Minor, consists partly of large tracts and ill-defined patches of irresolvable nebula, and of nebulosity in every stage of resolution, up to perfectly resolved stars like the Milky Way, as also of regular and irregular nebulae properly so called, of globular clusters in every stage of resolvability, and of clustering groups sufficiently insulated and condensed to come under the designation of “clusters of stars,” in the sense in which that expression is always to be understood in reading my Father’s and my own catalogues. In the number and variety of these objects, and in general complexity of structure, it far surpasses the Lesser Nubecula; some idea of which may be formed by comparing the numbers of registered nebulae and clusters in each. For while, within the limits assigned above to the latter, the number of such nebulae and clusters amounts only to 37, and taking in six outliers, which may be regarded as forming part of its system, at most to 4S, (a very remarkable con centration of such objects already, within an area not much exceeding ten square degrees),- the former within an area of about 42 square degrees, allows us to enumerate no fewer than 278 (without reckoning between 50 and 60 outliers, immediately adjacent, and which may very fairly be regarded as appendages of the nebulous system of the Nubecula Major) making an average of about 6½ to the square degree, which very far exceeds anything that is to be met with in any other region of the heavens. Even the most crowded parts of the stratum of Virgo, in the wing of that constellation, or in Coma Berenices, offer nothing approaching to it. It is evident from this, and from the intermixture of stars and unresolved nebulosity which probably might be resolved with a higher optical power, that the nubeculae are to be regarded as systems sui generis, and which have no analogues in our hemisphere.

“To the naked eye… the greater nubecula exhibits the appearance of an axis of light (very ill-defined indeed, and by no means strongly distinguished from the general mass) which seems to open out at its extremities into somewhat oval sweeps, recalling, in some faint degree, the appearance of that extraordinary object Mess. 27. It would be strange, indeed, but not beyond the analogies of other wonderful disclosures effected by optical improvements, if instruments yet to be created, or even possibly those already in progress, should one day analyse this last mentioned object into subordinate groups and systems of, perhaps, equal complexity. In the nubecula itself, there is a nebula (h. 2878) which, as will be seen in the description and remarks annexed to its observation in the Catalogue, has given rise to a similar train of speculation.

The only object which stands at all conspicuously distinguished from the general misty illumination of the greater nubecula (at least to my eye), is the great looped Nebula 30 Doradus of Bode, which, however, is merely to be perceived as a small indistinct patch, evidently not a star, and that only in fine nights. Of this object, an ample description has been already given, to which I shall here only add, that it is unique even in the system to which it belongs, there being no other object in either nubecula to which it bears the least resemblance…

The immediate neighbourhood of the Nubecula Major, is somewhat less barren of stars than that of the Minor, but it is by no means rich, nor does any branch of the Milky Way whatever form any certain and conspicuous junction with, or include it; though on very clear nights I have sometimes fancied a feeble extension of the nearer portion of the Milky Way in Argo (where it is not above 15° or 20° distinct) in the direction of the nubecula. On the whole, however, I do not consider this appearance as more than would be accounted for by the general increase of the number of small stars which, in almost every part of the course of the Milky Way, accompany its borders, and, in a telescope, announce its approach. I have encountered nothing that I could set down as diffused nebulosity anywhere in the neighbourhood of either nubecula.