Pre-telescope observations of the Large Magellanic Cloud

Seeing the Large Magellanic Cloud as pre-telescope observers saw it, with only their words and our eyes to aid us

Oral History

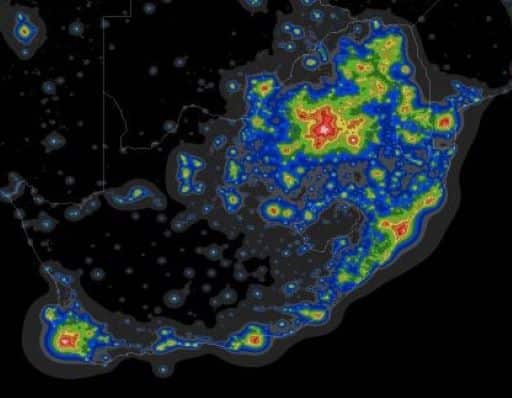

Looking like gossamer fragments detached from the Milky Way, the Magellanic Cloud’s ghostly light has beguiled mankind for untold eons. But the oral mythology in the ancient Southern Hemisphere cultures seems to have been lost to history. In my native southern Africa, the !Kung Bushmen said that the Large Magellanic Cloud was a part of the sky where soft thorn-less grass grows, like the kind they used for bedding. And the Sotho peoples saw the Clouds as the spoor of two stellar animals: the large cloud was Setlhako sa Naka, “The Spoor of the Horn Star” (Naka = Canopus) and the smaller cloud was Setlhako sa Senakane, “The Spoor of the Little Horn Star” (Senakane = Achernar).

The Clouds have a rich tradition in the cultures of Aboriginal Australians. In the Northern Territory, Ngalia spirits (called the Walanari) live in the Magellanic Clouds and throw hot stones to the earth in anger if someone reveals secret knowledge. In Western Australia, the LMC was the campsite of an old man, and the SMC was the campsite of his wife. The couple, known jointly as Jukara, had grown too old to feed themselves, so other star beings brought them fish from the sky river we know as the Milky Way. To the Kaurna people, the Clouds, being white, represent the ashes of the Blue Mountain lorikeet. These birds were assembled there by one of the constellations and were later treacherously roasted. The Yaraldi people believe there were two cranes who, knowing that the emus would hunt them and kill them, flew higher and higher until they reached the sky. They found it to be a good place to live, so they stayed there.

The Tupi-Guarani people, in the region of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, saw the Magellanic Clouds as fountains, with either a tapir (in the LMC) or a pig (in the SMC) drinking from it. The Mapuche people in Chile also saw the Clouds as ponds of water.

The Large Magellanic Cloud and the Coal Sack are roughly the same angular size and it looks like the LMC was brutally torn out of the fabric of the Milky Way and thrown over there, leaving behind a gaping hole of nothing. I have long wondered if any ancient cultures had an explanation for this. It appears the Incas did: their god Ataguchu, in a fit of temper, kicked the Milky Way and a fragment flew off, forming the Large Magellanic Cloud where it landed on the sky, and leaving the emptiness of the Coal Sack behind.

Abd al-Rahman al-Ṣūfī Shirazi (903-986)

Persian astronomer

Abd al-Rahman al-Ṣūfī Shiraz

Abd al-Rahman al-Ṣūfī Shirazi made the first recorded mention of the Large Magellanic Cloud. He ran an observatory in the Persian city of Shīrāz (now in Iran) and used the star catalogue in Ptolemy’s Almagest as the basis for his own book, Ketāb ṣowar al-kawākeb al-ṯābeta (“Book on the constellations of the fixed stars”). This appeared in AD 964, some eight hundred years after the original Almagest was written and was its first-ever updating. In it he gives a full description of the classical system of constellations, both according to the “scientific” Greek classification and to Arabic popular tradition. To this he adds his own observations and criticism of the traditions. This work is significant, not only for the complete description of the stellar sky, but even more for the valuable record of Ṣūfī’s own observations. He writes of the Magellanic Clouds:

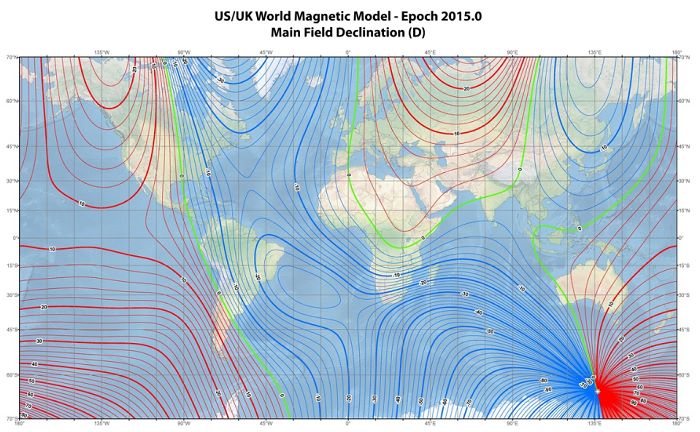

Unnamed others have claimed that beneath Canopus there are two stars known as the ‘feet of Canopus’, and beneath those there are bright white stars that are unseen in Iraq nor Najd, and that the inhabitants of Tihama call them al-Baqar [the White Ox of the southern Arabs as it is visible from Southern Arabia, although not from more northern latitudes], and Ptolemy did not mention any of this so we do not know if this is true or false.

Ahmad ibn Mājid (c1432 -c1500)

Arab navigator and cartographer

Ahmad ibn Mājid

Called “the Lion of the Seas” ibn Mājid was an Arab navigator and cartographer, raised in a family famous for seafaring. He was also an author, writing nearly forty works of poetry and prose, among which was As-Sufaliyya (1465) a nautical poem about Sofala, a port in what is now northern Mozambique. In it, he described the Magellanic Clouds, calling them the “clouds of the south pole.”

There are two White Clouds, brother: one is visible to the naked eye, the other one is faint. The position of the White Clouds is between Canopus and Sirius; but it is at a distance of ten fingers from Canopus, listen to my discourse, that is one arrow; and at a distance of two arrows from Sirius you can see both of them in straight line with the naked eye.

Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512)

Italian explorer, navigator, cartographer

Amerigo Vespucci

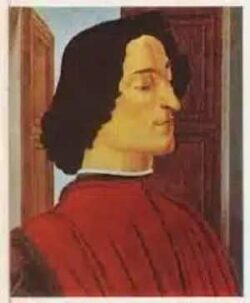

Amerigo Vespucci made the first European mention of the Clouds – and almost certainly the first diagram – in his Mundus Novus (“New World”), which was first published in 1503 and addressed to his patron, Lorenzo Pietro di Medici, about his voyage to the New World:

The sky and air are serene during a great part of the year. Thick vapours, with fine rain falling, last for three or four hours and then disappear like smoke. The sky is adorned with most beautiful signs and figures, in which I have noted as many as twenty stars as bright as we sometimes see Venus and Jupiter. I have considered the orbits and motions of these stars, and I have measured the circumference and diameters of the stars by a geometrical method, 126 ascertaining which were the largest. I saw in the heaven three Canopi, two certainly bright, and the other obscure. The Antarctic Pole is not figured with a Great Bear and a Little Bear, like our Arctic Pole, nor is any bright star seen near it, and of those which go round in the shortest circuit there are three which have the figure of the orthogonous triangle, of which the smallest has a diameter of 9 half-degrees. To the east of these is seen a Canopus of great size, and white, which, when in mid-heaven, has this figure:—

After these come two others, of which the half-circumference, the diameter, has 12 half-degrees; and with them is seen another Canopus. To these succeed six other most beautiful and very bright stars, beyond all the others of the eighth sphere, which, in the superficies of the heaven, have half the circumference, the diameter 32°, and with them is one black Canopus of immense size, seen in the Milky Way, and they have this shape when they are on the meridian:—

I have known many other very beautiful stars, which I have diligently noted down, and have described very well in a certain little book describing this my navigation, which at present is in the possession of that Most Serene King, and I hope he will restore it to me. In that hemisphere I have seen things not compatible with the opinions of philosophers. Twice I have seen a white rainbow towards the middle of the night, which was not only observed by me, but also by all the sailors. Likewise we often saw the new moon on the day on which it is in conjunction with the sun. Every night, in that part of the heavens of which we speak, there were innumerable vapours and burning meteors. I have told you, a little way back, that, in the hemisphere of which we are speaking, it is not a complete hemisphere in respect to ours, because it does not take that form so that it may be properly called so.

Peter Martyr d’Anghiera (1457-1526)

Italian historian of Spain and its explorers

Peter Martyr d’Anghiera

Working from original letters and documents, including those of Christopher Columbus, Peter Martyr d’Anghiera published his Decades of the New World (“De Orbe Novo Decades”) between the years 1511-1525. In the 1515 decade he wrote of the Clouds:

But it is most certeyne, that it is not gyuen to anye one man to knowe all thynges…Neuerthelesse, the Portugales of owre tyme haue sayled to the fyue and fyftie degree of the south pole: Where, coompasinge abowte the poynt thereof, they myght see throughowte al the heauen about the same, certeyne shynynge whyte cloudes here and there among the starres, lyke vnto theym whiche are seene in the tracte of heauen cauled Lactea via, that is, the mylke whyte waye.

Andrea Corsali (1487-?)

Florentine explorer

Andrea Corsali

Under the patronage of the Medici family in the service of the Portuguese, Corsali’s letter, “Lettera di Andrea Cosali allo illustrissomo Principe Duca de Medici, venuta Dellindis del mese di October nel XDXVI”; provides the only known narrative of a Portuguese voyage in 1515 down the African coast, around the Cape of Good Hope, and into the Southern and Indian Oceans, making landfall at Goa on the Indian coast. After rounding the Cape, Corsali observed the curious behaviour of an unrecorded group of stars which he described and illustrated… Crux.

Where is the Antarctic pole, … and evidently two clouds of reasonable size (the Clouds), which around it continuously now lowering and now getting up in circular motion they walk, with a star always in the middle, which with them yes it turns away from the pole about eleven degrees.”

Above these appeareth a marveylous crosse in the myddest of fyve notable starres which compasse it abowt (as doth Charles Wayne the northe pole) with other starres whiche move with them abowt .xxx. degrees distant from the pole, and make their course in .xxiiii. houres. This cross is so fayre and beautiful, that none other hevenly sygne may be compared to it as may appear by this fygure.

His letter includes the first drawing of the Southern Cross and the Magellanic Clouds. His sketch of the area around the south celestial pole showed the southern cross, top centre, with a tower-like pattern of seven stars to the left of it from which Plancius formed the constellation Polophylax. At right of centre are Alpha and Beta Centauri, the Pointers to the Southern Cross. Corsali’s diagram shows the sky as it would appear on a globe.

Antonio Pigafetta (c.1491 – c.1531)

Venetian scholar

Antonio Pigafetta

Famous for accompanying Ferdinand Magellan on his circumnavigation of Earth between 1519 and 1522, he was among the 18 men out of the original 270 who limped back to Spain in September 1522. Pigafetta related his experiences in his Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo (“Report on the First Voyage Around the World”) which was distributed to European monarchs in handwritten form. Although parts were published in Paris in 1525, the manuscript was not published in its entirety until the late eighteenth century. He described the Clouds thus:

The antarctic pole is not so covered with stars as the arctic, for there are to be seen there many small stars congregated together, which are like to two clouds a little separated from one another, and a little dimmed, in the midst of which are two stars, not very large, nor very brilliant, and they move but little: these two stars are the antarctic pole.

Edmond Halley (1656-1742)

English astronomer

Edmond Halley

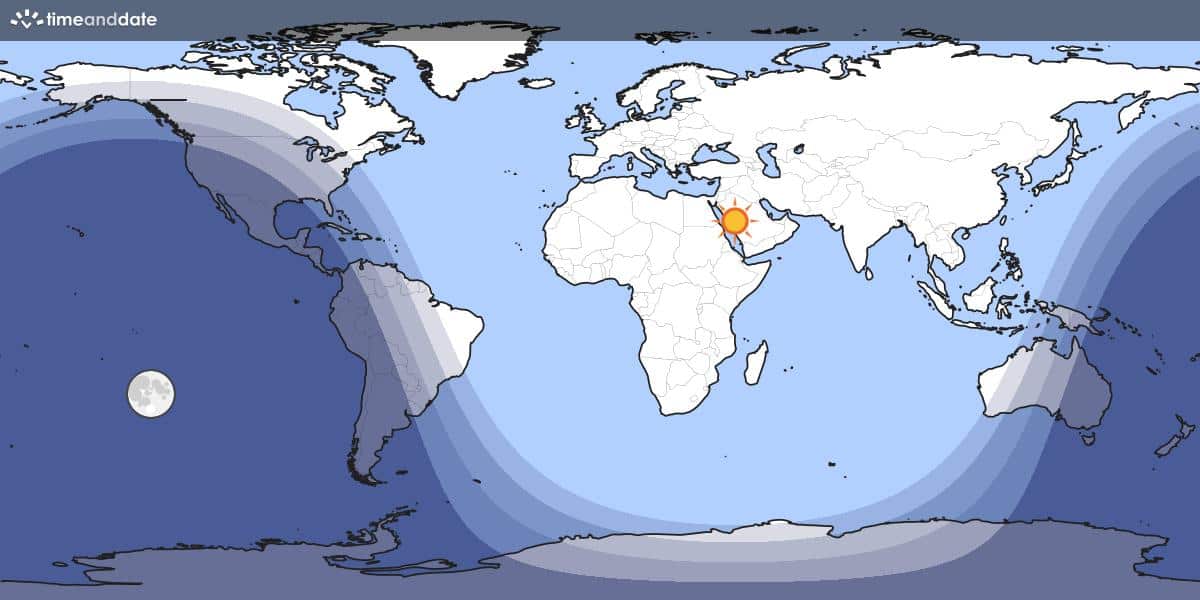

At 19 years old Halley embarked on a two-year trip to the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he set up an observatory with a large sextant with telescopic sights to catalogue the southern stars as Flamsteed was doing for those in the north. St Helena lies at a latitude of 15°55′ S and Halley had been told to expect clear skies on the island but alas, he was sadly disappointed for the skies are far more overcast than one would expect of a tropical island. He only managed to observe the positions of 341 stars in the Southern hemisphere, publishing his results in his “Catalogus stellarum Australium sive Supplementum Catalogi Tychonici” in 1679. However, he did observe the Magellanic Clouds and wrote:

The two Nubeculae called by the Saylors the Magellanick Clouds, are both of them like the whiteness of the milky way lying within the Antarctick Circle; they are small, and in the moon shine scarce perceptible; yet in the dark the bigger is very noticeable.

Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805)

Explorer, naturalist and chaplain

Pehr Osbeck

Pehr Osbeck was a Swedish explorer, naturalist and chaplain, and a student of Carl Linnaeus. He travelled to Asia in 1750-1752 and brought back some six hundred specimens that were included in Linnaeus’ Species Plantarum (1753). His account of his voyage, A Voyage to China and the East Indies, was published in Swedish in 1757, in German in 1765, and in English in 1771, edited and translated by Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-98). Volume 1 of this two-volume work includes a description of the Magellanic Clouds:

The two congeries of stars, of which the one which is near the Polus Eclipticae, is called Nubecula major, and the other Nubecula minor, are well-known to our East India navigators*. They observe how the one, which appears at night lower on the horizon, gradually mounts up higher than the other; and from this they can tell the hour of the night on the south side of the Line, as our common people can by the turning of the Great Bear.

* Our sailors call them the Magellanic clouds.