N157A

Tarantula Nebula

The intricate mosaic of dazzling nebulosity is staggeringly beautiful

Image credit ESO

RA: 05h 22m 07s Dec: -67° 56′ 46″

Diameter: 900 light-years

OB Associations: LH 100

NGC Objects: NGC 2069, 2070

This is one of the southern sky’s most stunning objects to observe. Stellar winds and supernovae have carved it into a spectacular display of arcs, pillars, and bubbles. There is nothing else like it in the sky. Credit: ESA/Hubble

Exploring N157A’s nebulosity

Exploring the Tarantula’s nebulosity is a magnificent and singular observing experience in any telescope, and it is the only object I know of whose visual appearance rivals photos – an intricate mosaic of dazzling light whose beauty no photograph can capture like the eye can. An eleven-year-old girl, Gabriella, put it best: after looking at Hubble images of the Tarantula I warned her that what she was going to see through my telescope was nothing like what Hubble could see. Sitting at my 16″ Dobsonian, she peered at the Tarantula in silence for a long, long time, then she said in hushed tones, “But this is so much better than Hubble!”

Without a filter the radiance of this exquisite object is spectacular! And with the UHC filter it is indescribable! It glows with every gradation of nebulous light and displays incredible depth and detail. Even with the filter its heart blazes with NGC 2070’s stars surrounded by an unsurpassed display of bright loops and arcs, streaming lanes of nebulosity and dark voids. The 3-D effect is phenomenal; the ridges incredibly sharply defined, and the rifts and ravines thrown into varying degrees of shadow. The dark voids resemble deep black lagoons surrounded by vast bright cosmic coral reefs with dramatic edges and filaments that curve and branch, and here and there jut back into the inky darkness. The spine of dark clouds appear as a few minuscule, spidery veins of darkness.

Tendrils of interwoven nebulosity lead the eye outwards from the Tarantula. Some eventually fade away into the surrounding sky, while others lead you to more treasures. A web of tendrils streams out from the southwestern side of the Tarantula, leading to the supernova remnant N157B then further southwest to the superbubble 30 Doradus C. The southern and western tendrils lead one straight towards the gigantic supergiant shell LMC 2. And one tendril leads northwards to NGC 2069.

NGC 2069 (Emission Nebula)

RA 05 38 42.0 Dec -69 00 30 Mag 10.1 Size –

228x: John Herschel described NGC 2069 as “the middle of a large extended faint nebulous mass which forms the northern branch of the great looped nebula, and is almost, or entirely, detached from it.” Without benefit of the UHC filter, the 3′ branch does indeed appear almost detached… but not entirely, a faint nebulosity tethers it to the rest of the vast complex. The branch of nebulosity itself is oval-shaped, bright and half a dozen mag 12-13 stars lie glinting in the nebulosity. With the UHC filter it appears clumpy and full of nuances of light, with a beautifully sharp western edge that runs N-S like a ridge of light.

NGC 2070 Super Star Cluster

RA 05 38 42.0 Dec -69 06 00 Mag 7.3 Size 3.5′

NGC 2070, home of the largest stars we know of in the universe. Credit: ESA/Hubble/NASA

At the heart of the Tarantula lies the young hot cluster NGC 2070 whose stellar inhabitants number roughly 500,000, and at its heart lies the compact cluster R136 which has birthed an overabundance of some of the most massive stars ever found. The intense radiation and strong winds of its stars along with that of many more within its vicinity produce enough energy to light up the vast Tarantula Nebula and make it visible to our naked eye here on Earth.

Clusters such as NGC 2070 have such an exceptionally high concentration of massive stars that they are referred to as super star clusters (SSC). They are rare examples of the super star clusters that formed in the distant, early universe, when star birth and galaxy interactions were more frequent. Containing hundreds of thousands to millions of young stars usually within less than a few parsecs, they are likely the progenitors of globular clusters. The stars of most young clusters drift away into the field star population within a few tens of millions of years, whereas the SSCs have enough mass to stay together for the long run, and NGC 2070 is one of the best candidates to hold together and eventually become a young globular cluster. (We have one such monster object within our own Galaxy – Westerlund 1 – it lies obscured behind a large cloud of dust and gas in the constellation Ara; an extremely difficult object to observe.)

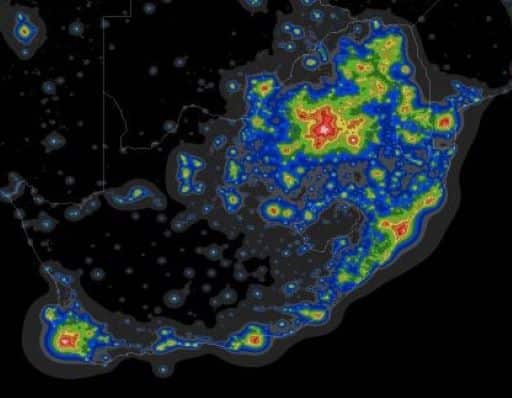

R136 appears as a mag 10 “star” at the heart of NGC 2070, but there is a whole lot more to it than meets the eye! In 1960 it was catalogued as the central “star” at the heart of the Tarantula by astronomers Feast, Thackeray, and Wesselink working at Radcliffe Observatory in Pretoria, South Africa.

In 1979 ESO’s 3.6m telescope resolved R136 into three components, R136a, R136b and R136c. R136a was listed as the most massive star in the universe. Hubble Space Telescope resolved R136a into at least a dozen massive, luminous stars forming a star cluster of record-breaking density, one of which – R136a1, a Wolf-Rayet star with a weight of 215 solar masses – is the new most massive star in the known universe. It also has the highest luminosity, close to 10 million times greater than the Sun.

The cluster also harbours many thousands of smaller stars. R136’s stars are extremely young, just 1 to 2 million years old which means that the earliest members of the human family, Homo habilis, had already developed the first stone tools before these stars were born.

A near infrared image of the R136 cluster, obtained at high resolution with the MAD adaptive optics instrument at ESO’s Very Large Telescope. R136a1 is resolved at the centre with R136a2 close by, R136a3 below right, and R136b to the left. Credit: ESA/Hubble

Observing NGC 2070 and R136

228x: NGC 2070’s dazzling congregation of stars is staggeringly beautiful. Crowded into a ~1.5′ region, the brilliant hoard of small glittering stars, too many to count and razor sharp against the glowing fusion of nebulosity and unresolved stars, blaze brilliantly in an ever-tightening throng to its heart wherein lies the dazzling 10th magnitude R136. It’s absolutely dumbfounding to stare at R136’s bright speck of light and try to envision it containing dozens of the universe’s most massive stars, along with the biggest of them all.

There are some other extraordinary stars that we can pick out with our telescopes among NGC 2070’s glittering pageant: mag 12.7 R134, a Wolf-Rayet star; two blue supergiants mag 12.5 R141 and mag 11.8 R142; mag 11.6 R140 which is a multiple star containing four components, of which two of the components, separated by 1.5″ are much brighter than the other two. And finally, mag 13.0 Melnick 34, the most massive binary whose two Wolf-Rayet components have identical spectral types of WN5h. Within 2-3 million years, both components are expected to evolve to stellar mass black holes which, assuming the binary system survives, would make Melnick 34 a potential binary black hole merger progenitor and gravitational wave source (Tehrani et al. 2019).

Hodge 301 (Open Cluster)

RA 05 38 16.0 Dec -69 04 00 Mag 10.9 Size 0.8′

Hodge 301 is as beautiful a little cluster in the eyepiece as it is in its photo; not least because of its stunning location Credit: ESA/NASA/Hubble

Hodge 301 is located 3 arcmin (~147 light-years) to the northwest of R136. It is the oldest cluster in the Tarantula, forming early on in the current wave of star formation, with an age estimated at 20-25 million years old, some ten times older than R136.

The two clusters provide astronomers with a direct comparison between the impact of supernova explosions and stellar winds on surrounding gases, as it is estimated that at least 40 stars within Hodge 301 have exploded as supernovae. The explosions have had two distinct consequences. Firstly, they have cleared out much of the gas and dust in Hodge 301, affording us a crisp view of the cluster. Second, the expanding supernovae shock waves have compressed gas on the outskirts of NGC 2070, helping to jumpstart star formation there. R136 on the other hand is young enough that none of its stars have yet exploded as supernovae. Instead, the stars of R136 are emitting fast stellar winds, which are colliding with the surrounding gases. More fireworks are on the way in Hodge 301 as it contains four red supergiants which will end their lives as supernovae within the next million years. That’ll be something to see!

Pietro Baracchi (1851-1926), an Italian-born astronomer who worked at Melbourne Observatory, discovered the cluster on 24 June 1884.

Objects are so often enhanced by their vicinity, and Hodge 301 exceptionally so… a beautiful little gathering of stars floating on the shore of the magnificent dark void, and the nebula’s undeniably 3D effect makes the little cluster look as if it’s shipwrecked against a cliff of nebulosity that is surging up from the dark void. Very gorgeous!! At 30″ in diameter, it is a wonderful little cluster to zoom in on with increasing magnification because of the way it gives up its stars – at 130x, the four stars Herschel recorded as an asterism are visible against the beautiful background glow of unresolved stars, although the north westernmost one is pretty faint. The grouping actually resembles a condensed Musca’s four-star fly body. At 228x, a couple more stars pop into view. At 333x there is the faintest hint of more stars although they maddeningly aren’t resolved and only reveal themselves by flickers that are gone as soon as they register on the brain.

SL 639 (Open Cluster)

RA 05 39 39.0 Dec -69 12 06 Mag 11.5 Size 1.0′

This lonely little cluster lies ~8′ NE from the Tarantula’s heart and small as it may be, it is certainly made more beautiful by its exotic location in the wispy outskirts of the Tarantula! The cluster’s age is ~10-15 million years, which is younger than Hodge 301. At 228x this cluster appears as a 50″, almost triangle-shaped, cluster of richly glowing, unresolved stars in which three small stars are resolved.

Small but pretty little SL 639 lying in whisps of the Tarantula’s nebulous web. Credit ESA/Hubble

Other extreme stellar exotica

In addition to the truly extreme stars in R136, here are some other extreme stars to observe:

VFTS 16: Most massive runaway star

RA 04 58 39.5 Dec -66 25 46 Mag 13.5

Runaway stars are massive O- and B- type stars found far from any OB association but whose velocities, based on proper motions and/or radial velocities, indicate that they originated in a nearby association. Runaway stars occur for a couple of reasons. A star may encounter one or two heavier siblings in a massive, dense cluster and get booted out through a stellar game of pinball. Or a star in a binary system may get a mighty kick from a supernova explosion when the more massive star explodes first and sends its sibling hurtling through space. O-type VFTS is the former, ejected from R136. Being only 1 million to 2 million years old, none of the cluster’s most massive stars have not yet exploded as supernovae. And it clearly got one hell of a boot out of the cluster as it is travelling at more than 400,000 kilometres an hour and has already travelled about 375 light-years.

VFTS 682: Massive “walkaway” star

RA 05 38 55.5222410976 -69 04 26 Mag 16

The location of VFTS 682 isolated star VFTS 682 and at the lower right is the very rich star cluster R136. Credit: ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

About 100 light-years to the northeast of R136 lies an isolated, extremely massive, luminous Wolf-Rayet star, VTS 682. Since very massive stars such as these have so far been found only in the crowded centres of star clusters, the exact mechanism for the formation of VFTS 682 remains a mystery. However, it is close enough to R136 that it might have formed there and been ejected. It has a space velocity lower than most runaways, which makes it a possible “walkaway” star – i.e. a slow runaway star. Interestingly, it has a near identical twin in the centre of R136

VFTS 352: Extreme overcontact binary

RA 05 38 28.4 Dec -69 11 19 Mag 14.5

The location of VFTS 352, lying amid the most glorious swirling nebulosity. ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

An overcontact binary is a binary star system whose component stars are so close that they touch each other or have merged to share their gaseous envelopes (also called a contact binary). VFTS 352 is the hottest, most massive overcontact binary known thus far. It is composed of two O-type stars whose centres are separated by just 12 million km. The stars of VFTS 352 are estimated to be sharing roughly 30% of their total mass between each other. No other overcontact binary is known to be this large or to share that great a percentage of its mass.

VFTS 399: High-mass X-ray binary hosting a neutron star

RA 05 38 33.4 Dec -69 11 59 Mag 15.8

At a faint mag 15.8, VFTS 399 may not be the most dazzling star to observe in the Tarantula, but it most certainly is among the most interesting! Clark et al. (2015) concluded that it is a high-mass X-ray binary hosting a neutron star! According to Ramírez-Agudelo et al. (2017) the O giant is known to be a rapid rotator.

R143: Luminous Blue Variable

RA 05 38 51.6 Dec -69 08 07 Mag 12.0

R143 was the first LBV discovered in the Tarantula. It was discovered to be a new LBV by Parker et al. (1993). Photometric and spectroscopic observations over the past 40 years indicate that during that time R143 moved red-ward (changing from an F5 to F8 supergiant), then blue-ward (possibly becoming as early as O9.5) and is now moving back to the red (currently appearing as a late B supergiant). Similarly, the V magnitude of the star has changed by at least 1.4 mag. Images of R143 show very unusual filaments of nebulosity extending from the star to a shell at a distance of 3.5 pc, perhaps due to a similar ejection mechanism that created the spiral jets and shell associated with AG Car, a Milky Way LBV

Four Wolf-Rayet stars and one other

Brey 72 (mag 11.5). Brey 88 (mag 12.9). Brey 89 (mag 11.1). Brey 90 (mag 12.2). And finally, a lovely sparkler, evolved supergiant R131, shining at mag 10.2.