Humboldt’s historical account of the Clouds

Humboldt tied all of nature, from outer space to the inner core of the planet, together

Alexander von Humboldt

Born: 14 September 1769 in Berlin in Prussia.

Died: May 6, 1859 in Berlin. He was buried at Schloss Tegel, the family home just north of Berlin.

Alexander von Humboldt

Humboldt was a Prussian polymath who is variously described as a geographer, naturalist, and explorer, but it is impossible to pigeonhole him. A brilliant observer and recorder of the tiniest details, he was also able to zoom out and see the bigger picture, mapping the relationships between biology, meteorology and geology. Immensely famous in his day, he published more than 36 books, travelled across four continents, and wrote well over 25,000 letters to an international network of colleagues and admirers.

Astronomer Maria Mitchell, who met Humboldt weeks before his death, marvelled in her diary that “no young aspirant in science ever left Humboldt’s presence uncheered,” and his ideas reverberate through her famous assertion that science is “not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.”

In 1847 he published volume four, A Physical Description of the Heavens, of his famous five-volume Cosmos, in which he attempted a description of all natural science (1847). In it he gives a fabulous historical account of the Magellanic Clouds:

We have next to speak in greater detail than could be done in the General View of Nature of an object unparalleled in the entire firmament, and which greatly enhances the picturesque beauty, so to speak, of the southern celestial hemisphere. The two Magellanic clouds (which were probably first called by Portuguese and then by Dutch and Danish navigators, Cape-Clouds), arrest the attention of the traveller, as I have myself experienced, in the most forcible manner, by their brightness, their remarkable isolated position, and their revolution at unequal distances round the southern pole. That the name which refers to Magellan’s voyage of circumnavigation was not their earliest designation is proved by the express mention and description of these luminous clouds by the Florentine, Andrea Corsali, in his voyage to Cochin, and by Petrus Martyr de Anghiera, Secretary to Ferdinand of Arragon, in his work de Rebus Oceanicis et Orbe Novo (Dec. i. lib. ix, p. 96). Both these notices belong to the year 1515, whereas Pigafetta, who accompanied Magellan, does not mention the “nebbiette” in the journal of the voyage previous to January.1521, when the ship Victoria made her way from the Patagonian Strait into the South Pacific Ocean. The older name of “Cape Clouds” is certainly not to be attributed to the proximity of the still more southern constellation of the Table-Mountain, which was itself only introduced by Lacaille. The name may more probably refer to the real Table-Mountain, and to the phenomenon, long dreaded by seamen as portending tempest, of a small cloud resting on its summit. We shall see presently that the nubeculae of the southern heavens, after having long been noticed but without receiving any name, as navigation extended and commercial routes became more frequented, gradually obtained names derived from those routes.

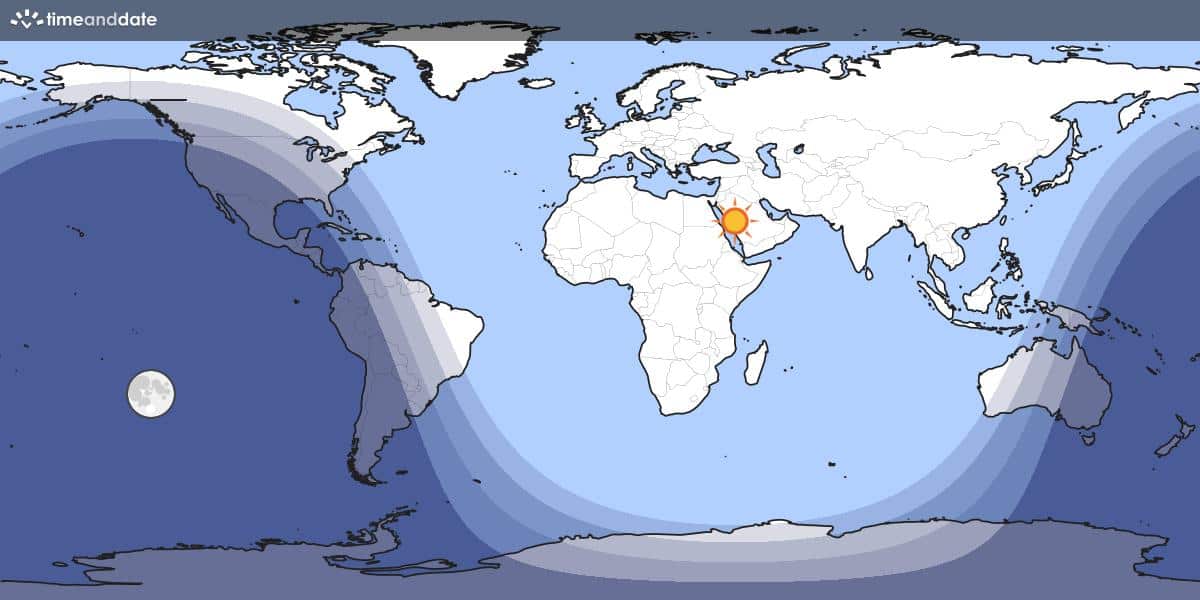

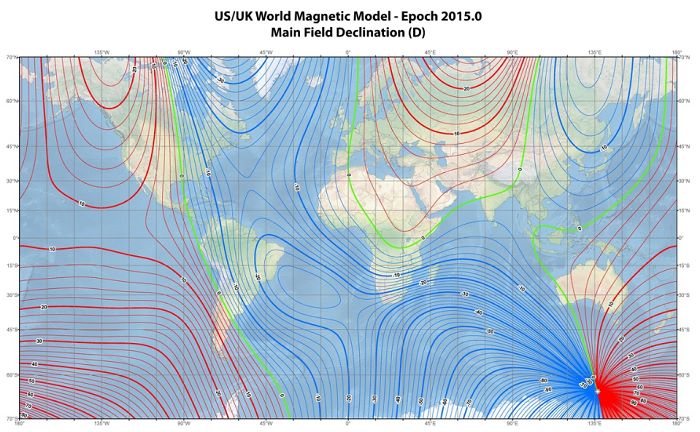

The frequent navigation of the Indian sea adjacent to the shores of Eastern Africa, especially from the time of the Ptolemies and in the voyages in which advantage was taken of the Monsoons, first made navigators acquainted with the constellations near the southern pole. As has been already remarked, it is among the Arabians that we find as early as the middle of the tenth century, a name for the larger of the Magellanic clouds which Ideler has identified with the (white) Ox, el-bakar, of the celebrated astronomer Dervish Abdurrahman Ṣūfī of Rai, a town in the Persian Irak. In the “Introduction to the Knowledge of the Starry Heavens,” written at the Court of the Sultans of the Dynasty of the Buyides, he says: “Below the feet of Suhel” (it is expressly the Suhel of Ptolemy, Canopus, which is here meant, although the Arabian astronomers also gave the name of ‘Suhel’, to several other large stars in the constellation of “el Sefina” or the Ship), “there is a white patch, which is not seen either in Irak,” (in the region of Bagdad), “nor in Nedschd,” (Nedjed, the northern and more mountainous part of Arabia), “but is seen in southern Tehama, between Mecca and the point of Yemen, along the shore of the Red Sea.”* The position of the “White Ox” relatively to Canopus is here assigned with sufficient accuracy for the unassisted eye; for the Right Ascension of Canopus is 6h 20m, and the eastern margin of the larger Magellanic cloud is in 6h 0m Right Ascension. The visibility of the nubecula major in northern latitudes cannot have been materially altered since the tenth century by the precession of the equinoxes, for in the course of the next ten centuries it reached its maximum distance from the north. Taking the most recent determination of the place of the larger cloud by Sir John Herschel, we find that in the time of Abdurrahman Ṣūfī it was perfectly visible as far north as 17° N. Lat.; at present it is so nearly to 18°. The nubeculae might therefore have been seen throughout the whole of the south-west of Arabia, the incense-producing country of Hadhramaut, as well as in Yemen, the ancient seat of civilization of Saba and of the early immigration of the Joctanides. The extreme southern point of Arabia, at Aden on the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, is in 12° 45′, and Loheia is only in 15° 44′ North Lat. The rise of many Arab settlements on the intertropical east coast of Mrica, both north and south of the equator, also naturally led to a more complete and detailed ac9uaintance with the southern constellations.

Of civilised navigators, the first who visited the West Coast of Africa beyond the Line were Europeans, and first, and more especially, Catalonians and Portuguese. Undoubted documents … shew that 178 years before the reputed first discovery of the Cabo da Boa Esperança (the Cape of Good Hope) by Bartholomew Di, in the month of May 1487, the triangular configuration of the southern extremity of the Mrican continent was already known. After Gama’s expedition, the rapidly increasing importance of the commercial route round the Cape, forming the general object of all voyages along the western coast of Africa, led to the two clouds or nubeculae being called by navigators the “Cape Clouds,” as being remarkable celestial phenomena seen in Cape voyages.

On the east coast of America, the continued attempts to advance southward beyond the equator, and even to the southern extremity of the continent, from the expedition of Alonso de Hojeda, which Amerigo Vespucci accompanied in 1499, to the expedition of Magellan with Sebastian del Cano in 1521, and that of Garcia de Loyasa* with Francisco de Hoces in 1525, had the effect of continually directing the attention of navigators to the southern constellations. According to the journals which we possess, and to the historical testimonies of Anghiera, this was especially the case in the voyage of Amerigo Vespucci and Vicente Yanez Pinzon, in which Cape St. Augustin, in 8° 20′ S. Lat. was discovered…. Petrus Martyr de Anghiera, who was personally acquainted with all the discoverers of that remarkable epoch, and whose letters are written under the vivid impression received by him from their narrations, depicts in an unmistakable manner the mild but unequal light of the nubeculae…. The great celebrity and long duration of Magellan’s voyage of circumnavigation (from August 1519 to September 1522), and the length of time during which the numerous party belonging to it remained under the southern heavens, obscured the remembrance of earlier observation, and the name of “Magellanic clouds” extended itself among the maritime nations bordering on the Mediterranean.

We have taken a single example of the manner in which the extension of the geographical horizon towards the South opened a new field to contemplative astronomy. Navigators advancing under these new heavens felt peculiar interest and curiosity in four objects: the search after a southern pole-star; the form of the Southern Cross, with its upright position when passing the meridian of the place of observation; the Coal-bags; and the revolving luminous clouds. From Pedro de Medina’s “Arte de Navegar” which appeared first in 1545, and was translated into many languages, we learn that as early as the first half of the sixteenth century meridian altitudes of the “Cruzero” were employed in determinations of latitude; measurement, therefore, soon followed simple contemplation. The first examination into the position of stars near the Antarctic pole was made by means of distances from known stars whose places had been determined by Tycho Brahe in the Rudolphine Tables: the credit of it belongs, as has been already remarked, to Petrus Theodori of Emden, and Friedrich Houtman of Holland, who sailed over the Indian seas in 1594. The results of their measurements were soon adopted in the star-catalogues and celestial globes of Blaeuw in 1601, Bayer in 1603, and Paul Merola in 1605. These were the feeble commencements of investigations into the topography of the southern heavens previous to Halley (1677) and previous to the meritorious astronomical endeavours of the Jesuit Jean de Fontaney, of Richaud, and of Noel. The histories of astronomy and of geography, in intimate connection with each other, bring before us the same memorable epochs as conducive alike to the completion of the general cosmical picture of the firmament, and of the outlines of the terrestrial continents.

The two Magellanic clouds, of which the larger covers forty-two and the smaller ten square degrees of the celestial vault, produce at first sight, as seen by the naked eye, the same impression as would be made by two detached bright portions of the Milky Way of corresponding dimensions. In strong moonlight the smaller cloud disappears entirely, while the larger one only loses a considerable portion of its light. The drawing given of them by Sir John Herschel is excellent, and accords perfectly with my most vivid Peruvian recollections. It is to the arduous exertions of the same astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope in 1837, that we owe the first accurate analysis of these wonderful aggregations of the most various elements. He found therein single scattered stars in great number ; groups of stars and globular star-clusters; and both regular oval, and irregular amorphous nebulae, more closely crowded than in the nebular zone of Virgo and Coma Berenicis. From the complex character of the nubeculae, therefore, they ought not to be regarded either (as is too often done) as extraordinarily large nebulae, or as detached portions of the Milky Way. In the Milky Way, round star-clusters, and more especially oval nebulae, are extremely rare phaenomena, excepting in a small zone situated between the constellation of Ara and the tail of Scorpio.

The Magellanic clouds are neither connected with each other nor with the Milky Way by any perceptible nebulous appearance. The smaller nubecula is situated in what, excepting the vicinity of the star-cluster in Toucani, is a kind of starless desert; the larger Magellanic cloud is in a less scantily furnished part of the celestial vault. The structure and internal arrangement of the larger nubecula are so complicated, that masses are found in it (like No. 2878 of Herschel’s Catalogue), in which the general form and character of the entire cloud are exactly repeated. The conjecture of the meritorious Horner, of the nubeculae having once been parts of the Milky Way, in which their former places can still be recognised, is nothing more than a myth; nor is the assertion of a progressive motion or change of position being perceptible in them from the time of Lacaille, better founded. The indefiniteness of their edges as seen in telescopes of small aperture had caused the positions formerly assigned to them to be inexact, and it has even been remarked by Sir John Herschel that nubecula minor is entered almost one hour in Right Ascension out of its true place in celestial globes and star maps generally. According to the same authority, nubecula minor is situated between the meridians of 0h 28m and 1h 15m, and between 162 ° and 165 ° north polar distance; and nubecula major in 4h 40m-6h 0m R.A., and 156°-162° N.P.D. Of stars, nebulae, and clusters, he has given in Right Ascension and Declination no fewer than 919 in the larger, and 244 in the smaller nubecula. In order to distinguish the three classes of objects from each other I have counted up in the list :-

In nubecula major, 582 stars, 291 nebulae, 46 star-clusters

In nubecula minor, 200 sfars, 37 nebulae, 7 star-clusters.

The smaller number of nebulae in the nubecula minor is striking; their proportion to the nebulae in nubecula major being as 1 :8; while the corresponding ratio of single stars in the two nubeculae is about as 1:3. These tabulated stars, almost eight hundred in number, are mostly of the 7th and 8th magnitudes, some being between the 9th and 10th. In the midst of the nubecula major there is a nebula noticed as early as by Lacaille, (30 Doradus,. Bode, No. 2941 of Sir John Herschel,) which is without a parallel in any part of the heavens. It hardly occupies 1/500th of the area of the entire nubecula, and yet, within this space Sir John Herschel has determined the positions of 105 stars from the 14th to the 16th magnitude, which are projected against or detach themselves from the altogether unresolved, uniformly shining, and unchequered nebulous ground.

Opposite to the Magellanic luminous clouds, and at a greater distance from the Southern Celestial pole, there revolve around it the black spots or patches which at an early period, at the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth centuries, attracted the attention of Portuguese and Spanish Navigators.

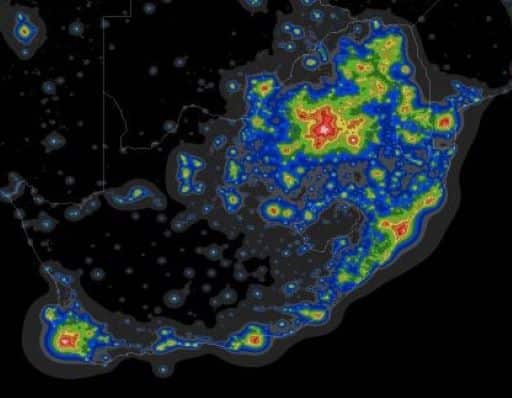

. . . The phenomenon of this class which has been longest known, and which is most striking to the unassisted eye, viz. the dark patch in the Southern Cross, is situated on the eastern side of that constellation, and is pear-shaped, with a length of 8 and a breadth of 5 degrees. There is in this large space one star visible to the naked eye, (between the 6th and the 7th magnitude), and a large number of telescopic stars from the 11th to the 13th magnitudes. A small group of 40 stars occupies nearly the centre of the space. Paucity of stars and contrast with the surrounding brightness have been assigned as the causes of the sensible blackness of the space in question; and since the time of Lacaille this explanation has been generally received…. Whilst I remained under the southern tropic, and under the influence of the powerful impression made upon me by the aspect of the celestial canopy towards which my attention was continually drawn, the above explanation, from the effect of contrast, appeared to me, probably erroneously, to be an unsatisfactory one.

* Lacaille, in the Mem. de I’Acad. annee 1755, p. 195.