Bubbles, Superbubbles & Supergiant Shells

Searing winds and titanic explosions

The power of massive stars

Massive stars dynamically shape the interstellar medium around them on timescales of a few million years via UV radiation, stellar winds and ultimately their supernova explosion deaths. Three distinct classes of objects are powered by these stars – bubbles, superbubbles and supergiant shells.

Bubbles

Bubbles are blown by the searing stellar winds of individual massive stars. They range in diameter from fractions of 1 pc to a few x10 pc.

Bubbles evolve along with the central stars as their formation is dependent on the evolution and mass loss history of the central massive star. During the Main Sequence phase, a massive star is surrounded by the interstellar medium. It loses mass via tenuous fast stellar wind, thus its wind-blown bubble contains interstellar material and is an interstellar bubble.

As the massive star evolves into the Red Supergiant phase (copious slow wind) or Luminous Blue Variable (copious slow or not-so-slow wind), the copious mass loss forms a small circumstellar nebula inside the cavity of the main sequence bubble.

As they race through their lifecycles, the brief Wolf-Rayet phase represents the most advanced evolutionary stage in the lives of luminous massive stars. A Wolf-Rayet star sheds mass rapidly by means of very fast stellar winds that sweep up the circumstellar material, thus its wind-blown bubble contains stellar material and is a circumstellar bubble.

N44F

Blown by an O-type star

Size: 11 pc

N44F. Credit: NASA, ESA, Y. Nazé (University of Liège, Belgium)

N57C = NGC 2020

Blown by a Wolf-Rayet star

Size: 28 pc

N57c = NGC 2020. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI

Superbubbles

The combined stellar winds and subsequent supernovae explosions of the entire OB association’s massive members work together to create a superbubble, with a diameter of ~100 pc. (In a typical OB association roughly one supernova per million years occurs, and this rate will remain approximately constant over 50 million years – the lifetime of the lowest mass B stars likely to become supernovae).

As the hot and compressed bubble of material expands it ploughs into the surrounding material, compressing it and triggering new star formation at the edges of the superbubble. So while destructive forces shaped the superbubble, new stars are forming around the edges where the gas is being compressed. Like recycling on a cosmic scale, this next generation of stars will breathe fresh life into the supperbubble.

N11

Size: 150 x 100 pc

N11. Credit: NASA; C. Aguilera, S. Points, and C. Smith (CTIO); and Z. Levay (STScI)

Supergiant Shells

Whereas a superbubble requires only one episode of star formation, a supergiant shell (SGS) requires multiple generations of star formation. They are the largest interstellar structures in a galaxy, having diameters an astounding 1,000 pc (3,260 light-years) and greater. Their diameters often exceed the scale height of the galactic gas disk, allowing them to puncture the gas disk and vent their hot interior gas into the galactic halo.

SGSs have OB associations along the periphery or in the centre, with younger OB associations more often found along the periphery. After roughly 12 Myr, if no new OB associations have been formed, a SGS will cease to be identifiable at visible wavelengths.

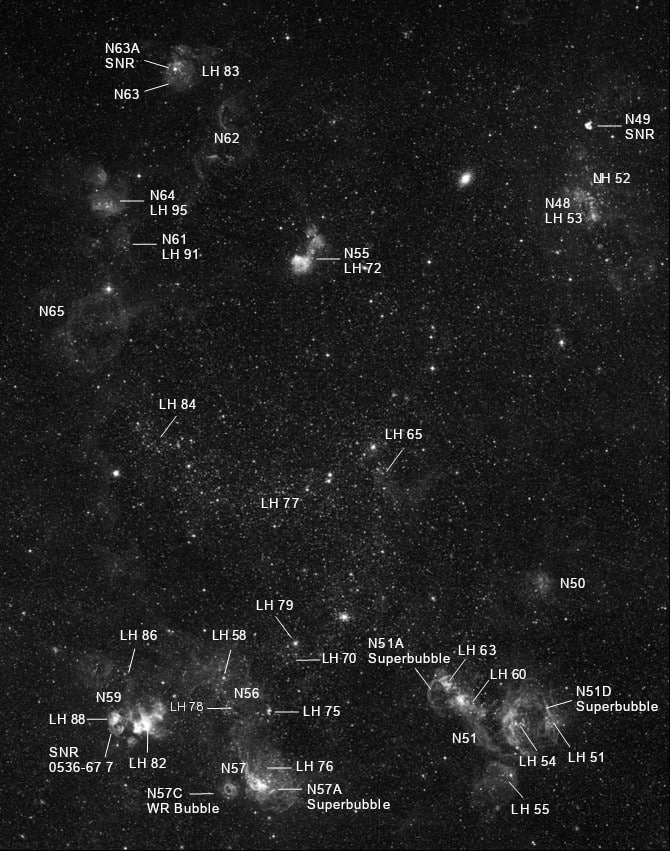

LMC 4

Size: 1500 pc

LMC 4. DSS image

LMC 4… A superb example

The supergiant shell LMC 4 is a superb example illustrating the relative sizes of bubbles, superbubbles and a supergiant shell.

The image of LMC 4 shows recent star formation activity along its rim. The stellar energy feedback has produced bubbles, and superbubbles, as well as prominent HII regions and supernova remnants.

LMC 4 and its periphery

LMC 4’s central shell cavity is mostly evacuated, and within it, the most prominent OB association is the enormous LH 77, also known as the Quadrant (290 pc in size). This association has an older stellar population, as it has already expelled its ambient gas, and has most likely contributed to the formation of LMC 4.

Along the periphery of LMC 4 are several young OB associations still within H II regions. These include LH 83, LH 91, and LH 95 in the northeast, and LH 52 and LH 53 in the northwest along the impact zone where the enormous LMC 4 is colliding with the smaller LMC 5 to its west.

A most mysterious young OB association, LH 72 and H II region N55, lies in the centre of the cavity.

The bubble N57C = NGC 2020 is blown by the single massive Wolf-Rayet star, Brey 48 and is ~25pc in diameter.

LH 63 is responsible for creating superbubble N51A (65 x 50 pc in size).

LH 54 is responsible for creating superbubble N51D (135 x 120 pc in size).

LH 76 is responsible for creating superbubble N57A (135 x 105 pc in size).

Two SNRs lie along the periphery – N63A in the NE and SNR 0536-67 7 in the SW. The bright SNR N49 in the NW appears as if it is part of LMC 4’s periphery but Fujii et al. (2018) determined that the SNR is actually associated with LMC 5 alone.