SN1987A: The Cloud’s Spectacular Supernova

In 1987 we had an incredible front-row seat to a cosmic event that isn’t rare… but rarely happens near us

Image credit ESO

RA: 05h 35m 28.0s Dec: -69° 16′ 11″

Diameter: 1.37 light-years

Local OB Associations: –

NGC Objects: –

A Spectacular Supernova

In 1970 the American astronomer Nicholas Sanduleak catalogued an 11.7 magnitude star located at the edge of the Tarantula Nebula as Sanduleak -69°202. The star is logged as blue. There was nothing special about the star. It did not vary in light output. It did not have any anomalous emission lines. It did not seem to be shedding mass at an especially noticeable rate or in a special way. Indeed, there was nothing special at all about Sanduleak -69°202 until it blew itself to smithereens. And then it became very special!

The closest supernova since Johannes Kepler recorded his observations of a supernova in the year 1604, the light from its violent self-destruction reached Earth on February 23, 1987. Since then an armada of telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope (which wasn’t even in space when the supernova was discovered), has studied it, giving astronomers an intimate look at one of the most fundamental and powerful drivers of evolution in the universe, and allowing them to study the phases before, during, and after the death of a star, and its observations have provided much insight into core-collapse supernovae.

Photographs of the Large Magellanic Cloud, before (left) and after (right) the explosion of SN1987A. The supernova is visible on the right image just below the Tarantula Nebula. Credit ESO

The glorious ESO Schmidt Telescope image of the supernova (the bright star middle right). At the time of this image, the supernova was visible with the unaided eye. Credit ESO

The Supernova’s Timeline

February 23, 1987, at 07h 35m 35s…

After whizzing through space for 163,000 years and a couple of hours ahead of the light front, the neutrinos from SN 1987A swept over Earth. At 07h 35m 35s Kamiokande II (a neutrino telescope located in the Kamioka mine in Japan) recorded the arrival of 9 neutrinos within an interval of 2 seconds, followed by 3 more neutrinos 9 to 13 seconds later. They had penetrated the Earth from the direction of the Large Magellanic Cloud. Simultaneously, the same event was revealed by the IMB detector (located in the Morton-Thiokol salt mine near Faiport, Ohio) that counted 8 neutrinos within about 6 seconds. A third neutrino telescope (the “Baksan” telescope, located in the North Caucasus Mountains of Russia, under Mount Andyrchi) also recorded the arrival of 5 neutrinos within 5 seconds of each other.

Kamiokande II (a neutrino telescope located in the Kamioka mine in Japan) recorded the arrival of 9 neutrinos within an interval of 2 seconds, followed by 3 more neutrinos 9 to 13 seconds later. Credit: University of Tokyo

February 23, 1987, two hours later…

The light from the exploding star reaches Earth. Canadian astronomer Ian Shelton was at Las Campanas in Chile observing stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Studying a photographic plate of the LMC later that night, he noticed a bright object that he initially thought was a defect in the plate. But when he showed the plate to other astronomers at the observatory, he realized the object was the light from a supernova! Oscar Duhalde, one of the night assistants, mentioned that he had noticed that there was a new light in 30 Doradus when he stepped out earlier for a cigarette… the supernova was still faint at the time, merely a few hours old.

As Shelton later remarked, “..… of course confirmation comes by putting on your coat, walking outside and looking UP!” So the four astronomers (Shelton, Duhalde, Barry Madore and Robert Jedrzejewski) promptly went outside to see for themselves if this was a new supernova. And a supernova it was! They knew this immediately; it was far too bright to be a simple nova in the LMC. Shelton had to notify the astronomical community of his discovery. With no Internet in 1987, the astronomer scrambled down the mountain to the nearest town and sent a message to Brian Marsden at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, MA. Marsden was director of the IAU’s Central Bureau of Astronomical Telegrams, a service that keeps astronomers abreast of the latest astronomical discoveries and developments.

Ian Shelton with the discovery plates

A third independent sighting came from amateur observer and AAVSO member, Albert Jones in Nelson, New Zealand. In his own words: “I was monitoring some stars not far from the Tarantula Nebula. On that fateful night, while I was observing stars elsewhere in the sky, I noticed some clouds coming over so I poked the telescope at my targets in the LMC. I was quite surprised to see a bright stranger, so I noted its position on the chart. But before I could make a magnitude estimate the clouds moved over. I phoned Bateson who started phoning others for confirmation. Then the clouds moved away and I made an estimate of the stranger before phoning Bateson again to tell him. He then phoned the Observatory at Siding Spring, in Australia, to tell them about the star. I have been told that everyone at the Observatory stopped what they were doing and turned their attention to the supernova. Rob McNaught then checked the photos he had taken and found the star was recorded on them. Rob then phoned Dr. Marsden to say he had a photo of it, but as Brian was already on the phone to Chile, Rob told the secretary. Dr. Marsden then phoned back to Rob to congratulate him on the discovery, but Rob said he was not the discoverer. It was discovered by someone in NZ, but did not know who it was. Dr. Marsden correctly guessed who it might be.”

A legendary variable star observer, Albert Jones is shown here alongside the telescope he built in 1948 and with which he made all his observations. He was awarded an OBE and honorary doctorate of science in recognition of his contribution to astronomical programmes

Meanwhile in Australia, astronomer and comet-finder Rob McNaught was also photographing that area of the sky. He went to bed without developing his plates… and awoke the next day with the astronomical world full of news of Shelton’s announcement. When he developed his image, he found that he had the first permanent recording of the light from the supernova.

AAVSO Alert Notice 92 was released on February 25, 1987, alerting observers to the new discovery. Immediately after the supernova was announced, literally every telescope in the southern hemisphere started observing this astonishing new object.

Four days later…

For the first time ever, the availability of pre-existing data provided the first chance for astronomers to posthumously identify the progenitor star… and it was tentatively identified as Sanduleak -69°202. (After the supernova faded, that identification was definitely confirmed by Sanduleak -69°202 having disappeared!)

This presented the first big surprise, for Sanduleak 69°202 was a blue supergiant. Everyone expected that the exploding star would be a red supergiant. No one anticipated that the first nearby supernova would be an everyday B3 supergiant with a relatively modest mass! For a time astronomers thought that Sk -69° 202 might be just a foreground star, and that a red supergiant lurked behind it. But the two-hour delay between neutrino detection and the optical outburst was consistent with the relatively small radius appropriate to a B star.

The star was originally charted by the Romanian-American astronomer Nicholas Sanduleak (1933-1990) in 1970

Spectacular Light Echoes

One impressive phenomena related to the supernova, are the light echoes. When a star has a bright outburst, the light may illuminate clouds or sheets of interstellar dust in its vicinity and along the line of sight to us. The arrival of the scattered light is delayed from the arrival of the direct signal, resulting in apparent rings that expand in time.

Credit: Anglo-Australian Observatory

This image was taken 1997 and although the stellar detonation had been seen more than a decade before, light from it continued to bounce off nearby interstellar dust and be reflected to us, thus making the spectacular light echoes of the mighty supernova.

SN1987A’s spectacular light show…

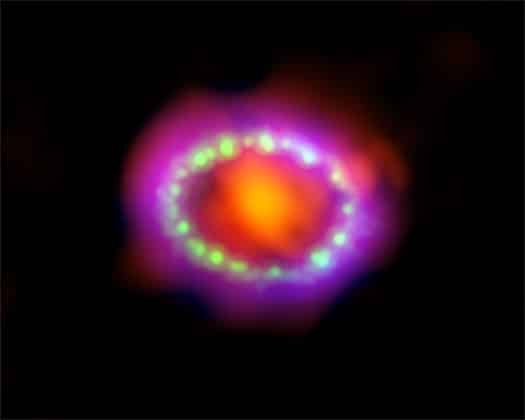

Credit: Hubble Space Telescope

Hubble has recorded the celestial drama unfolding at the stellar demolition site by taking photographic and spectrographic information every year. The shock wave unleashed during the supernova explosion raced toward a ring of matter encircling the blast site. Astronomers used Hubble to monitor the ring for signs of the impending bombardment. They detected the first evidence of a collision in 1996 (the bright spot at 11 o’clock in the Feb. 1998 image]. Subsequent observations show dozens more “hot spots” as the blast wave slammed into the ring, compressing and heating the gas, and making it glow. The ring, about a light-year across, already existed when the star exploded and is a fossil record of the final stages of the star’s existence. Astronomers believe the star shed the ring about 20,000 years before the supernova blast. The bright spot at 4 o’clock is a foreground star photobombing the supernova in spectacular fashion.

A supernova Venn Diagram! Credit ESA Hubble Space Telescope

The light from the supernova heated the gas in the ring so that it glows at temperatures from 5,000 to 25,000 degrees Kelvin. It is not clear what is causing the two larger, fainter rings. The two bright objects are stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The image was taken in 2010.

Credit: Hubble Space Telescope and Hubble Heritage Team

The Tarantula Nebula’s glittering stars and swirling gas form a spectacular backdrop for a star that blew itself up.

t

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/PSU/D. Burrows et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI; Millimeter: NRAO/AUI/NSF

In February 2017, this gorgeous image was released to commemorate the 30th anniversary of SN 1987A. It combines data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory, as well as the international Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), allowing us to see SN 1987A like never before.

Thirty-two years later…

For 32 years astronomers were beguiled by one of the enduring mysteries of 1987A: What became of the neutron star that formed at the heart of the explosion? Astronomers thought that the neutrino signal meant that a neutron star formed, but despite over three decades of searching with many different types of telescopes, there was no sign of it. Since nobody could find it, different reasons were advanced for why it wasn’t there. Some wondered if SN 1987A formed a quark star instead of a neutron star. Another theory suggested that a pulsar (all neutron stars are pulsars but not all pulsars are neutron stars) was formed instead, and that its magnetic field was small or unusual, preventing us from detecting it. A third possibility was that gas and dust fell back into the neutron star, collapsing it into a black hole. A simple explanation was that it was there, just obscured by so much gas and dust that we couldn’t see it.

Occam’s Razor wins again: On November 19, 2019, astronomers reported in the Astrophysical Journal that observations from the ALMA radio telescope provided the first indication of the missing neutron star after the explosion emerging from a thick cloud of dust which had completely obscured it for 32 years. Extremely high-resolution images revealed a hot “blob” in the dusty core of SN 1987A, which is brighter than its surroundings and matches the suspected location of the neutron star.

“We were very surprised to see this warm blob made by a thick cloud of dust in the supernova remnant,” said Mikako Matsuura from Cardiff University and a member of the team that found the blob with ALMA. “There has to be something in the cloud that has heated up the dust and which makes it shine. That’s why we suggested that there is a neutron star hiding inside the dust cloud.”

Thirty-seven years later…

Using the infrared capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope to peer behind the dust cloud that remains where there once was a star. There, they found a neutron star, a dense ball of matter only around 20 kilometres from end to end, yet weighing 1 1/2 times our sun.

Supernova 1987A, imaged by the Hubble and JWST. The purple-blue source in the centre is the emission detected with the JWST/NIRSpec instrument. Credit: Hubble Space Telescope WFPC-3, James Webb Space Telescope NIRSpec, J. Larsson

Observing where Sk -69° 202 blew up

Lying 5.5 arcmin southwest of the superbubble 30 Doradus C, the remnant is, 37 years later, visible in large telescopes at high magnification! I cannot imagine the thrill of seeing it! (And how astronomically incredible is it for people to have seen the supernova and its remnant?) I search for it on a regular basis, but alas, it still seems to be out of the reach of my telescope.

Nonetheless, it’s a remarkable observing experience to peer at the spot where Sanduleak -69°202 blew up and consider how, over the last 37+ years, its titanic supernova has done an unprecedented thing – shown us cosmic change on a human timescale: a star was destroyed, new elements were created, and a tiny corner of the cosmos was forever altered.

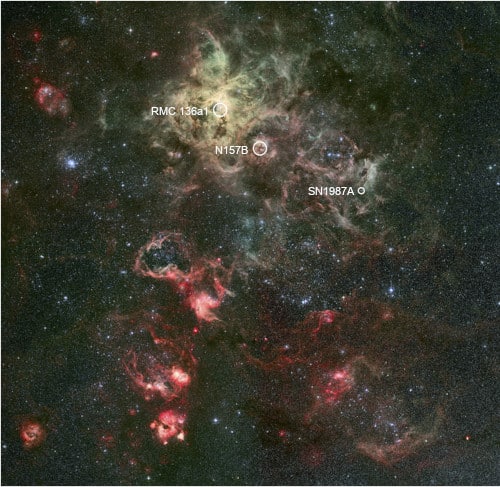

This image of the Tarantula Nebula and its surroundings shows the location of the closest supernova to Earth to have been observed since the invention of the telescope (SN1987A)… the remnants of another supernova that occurred around 5,000 years ago from our point of view (N157B), and also the heaviest star ever discovered (RMC 136a1, within the super star cluster RMC 136) that will one day go supernova in spectacular style. Credit: NASA, ESA, ESO